Competing as a protagonist in the digital, global market, means delivering actual value to customer, always striving to improve speed, quality and adaptation. The performance of the work teams that produce those results, is obviously one of the key factor in achieving these standards. Agile suggests, to reach that objective, to design teams which are self-managing, cross-functional, co-located, and long-lived. In this post we want to reason about stable teams, their advantages and, if any, difficulties or myths.

We strongly believe that creating stable and long-lasting agile teams, is a key-competitive element for companies, who want to deliver continuous stream of value to their customers.

Stable teams develop, over time, stronger behavioral and working dynamics, higher levels of transparency that favor trust and collaboration among its members; when facing complexity, trust within the team actually drives increased levels of performance, creativity and intrinsic quality of the product the team is dealing with.

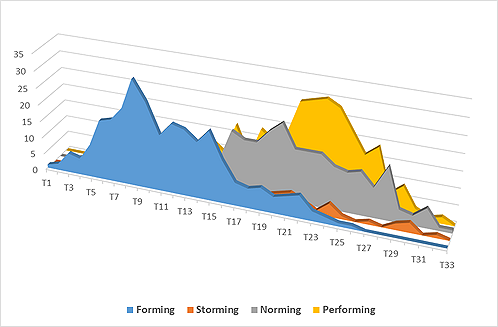

To reach this state, a team needs to pass through a series of developing steps. A model that is largely used to describe this evolution, is the Tuckman Stages model.

This post, then, will also go through some weakness areas of that model, and how to assure performance for agile teams in contexts where stability is not assured, by exploring the 60-30-10 heuristic.

Tuckman Stages Model

In 1965, Bruce Tuckman, developed and published a research about the interactions between the people belonging to a group, and its following development as a team; this study eventually led to the creation of a model that took his name.

That model involves the following phases:

- Forming: it represents the initial phase where, among the team members, the development of a first sense of belonging takes place; they share common values, align to the corporate mission, live first joint experiences and prepare themselves to trust each other, as the foundation to be successful

- Storming: phase in which conflicts can occur due to the attempt of individual team members to find their place and “impose” their individuality and leadership

- Norming: having successfully passed the previous step (which shouldn’t be taken for granted), the team defines proper norms, working methods, and refines roles and responsibilities. The sense of unity initially only perceived, is now established and individuals feel themselves actually part of a whole: the team

- Performing: finally the team has achieved sufficient stability to deliver continuous business value and achieve results. The team is now able to manage itself in improving its process and working practices

The model presents a logical sequence of phases and clearly shows the impact of each one on productivity.

In practice, though, it has some weakness areas. First of all we could think that the phases are discrete and linear in their development. However, that’s not the reality.

“Scientific community emphasized that this model should be considered more a conceptual declaration”

According to the context, the people involved and the work that must be done, the team can pass from one phase to the other more or less quickly, and have regressions. Performance trends are not always that “smooth” in their descending and ascending, but could have continuous up and down peaks.

It is worth noting that in the following years, the scientific community emphasized that this model should be considered more a “conceptual declaration” than a fact; it was conceptualized and brought to life by the data collected by the author’s studies, which actually lacked, and seems still lacks, an empirical validation on the ground.

Getting rid of Tuckman’s Model

A study conducted by the US Defense Ministry in collaboration with the Defense Acquisition University, shows that in teams formed by a few members, with strong competence and motivation, the phases described by the Tuckman model, actually strongly overlap.

The Storming stage would be very limited in its wideness but extended in time, so as to be called “Brainstorming“: moments in which the team reflects productively on how to become more effective and evolve its ways of working. Additionally, it seems that the Norming phase continues to happen until the end of the measured endeavor.

Agile Teams: acrobats on uncertainty

Agile teams are small ones (no more than ten), technically and business competent and, by design, they are given the autonomy to decide their ways of working. Furthermore, they are cross-functional, which increases the overall internal competence and, finally, they are physically or “digitally” co-located, which definitely favors communication and adaptation among members.

They systematically hold retrospectives which helps to adapt and adjust their process in order to become more effective over time (see Brainstorming phase observed in the previous example).

Additionally, these teams are open and transparent enough to review and amend their norms and rules, as soon as they are no more effective, actually confirming that the Norming phase lasts until the very end of the project.

It seems, indeed, that Agile teams naturally fit very well in that situation. But, what about stability and not changing their composition?

“Due to the high volatility and fluidity of the markets, team stability is strongly challenged”

We know that adding or moving team members breaks stability and forces the team to review its dynamics and create new ones: this produces inefficiencies, reducing motivation.

We know, however, that due to the high volatility and fluidity of the markets, team stability could be strongly challenged for the following reasons:

- new skills can be necessary to teams,

- ans/or necessity to increase capacity of the team,

- and/or people change job more frequently

- and/or re-organizations could take place with a smaller cadence than in the past;

to such an extent, Agile teams need to be adaptive and fast also in rearranging themselves.

Said and acknowledged that, are there any prerequisites to check or good practices to put in place, to help teams remaining effective even when stability is at risk?

Getting off, on the right foot

It seems, actually, that there is another important element which influence the stability of teams: how teams are designed. A bad design could lead to significant problems in efficiency, quality of work and conflicts between members.

Richard Hackman and Ruth Wageman coined a heuristic which helps to think on how to start with the right foot from the very beginning; this is the “60-30-10 Rule for Coaching Teams“.

The heuristic explains the percentages of time/energies that should be dedicated to the following activities:

- 60% on how a team is designed,

- 30% on how it is launched,

- 10% on how the team is coached.

Team Design, Launching and Coaching

When it’s time to design a team, it is necessary to focus on some pre-work.

“Bad performance of a team could lead to eventually re-shuffle it, which brings us to hit the same problem we are trying to solve: instability of teams”

It is firstly necessary to understand if there’s enough of homogeneous work in the portfolio, to create a stable team. The suggestion is to create teams which are dedicated to one or more products that belong to the same stream of value for the selected category of client.

Then, it is necessary to create a first draft mission for that team (which will be reviewed and refined by the actual team when formed), delineate what business objectives it needs to achieve, appoint a Product Owner, understand what skills are necessary and roughly estimate (range) how many of people should be involved.

Usually happens that teams are designed by managers, who move people around according to their actual capacity, competence and also speculating on personal relationship among them. The risk here, is that managers do not actually have all the relevant information to make the right decision and, also, they could have any biases which has the potential to badly influence their conclusions.

We know that bad performance of a team could lead to eventually re-shuffle it, which brings us to hit the same problem we are trying to solve: instability of teams.

One good practice is self-selecting teams. The idea is to let the people select the teams to which they want to belong, through attending to dedicated workshops.

“Even when the team stability is at risk, they self-arrange and look for the best solutions to find another status of balance and remain effective”

During these workshops, flip-charts are hung to the walls containing all the relevant information about the mission/objectives and the constraints (a few) that must be respected for each team (e.g. max number of people, any diversity factors, end-to-end delivery capability, etc.). Product Owners stand beside them, ready to reply to any questions.

People walk around, talk to the Product Owners, discuss to each other in order to look for the best team where, each one, can deliver value and then they stick their image/avatar on the respective team flip-chart. Product Owners and mangers, then, facilitate the discussion in order to arrive to the final refinement and adjustments of teams composition.

This approach considerably increments the accountability, motivation and resilience of the team members. One positive result is that, even when the team stability is at risk, they self-arrange and look for the best solutions to find another status of balance and remain effective.

Once the team is designed, the next stream of energy must be devoted to team launching.

In that moment it is paramount to clarify any doubts the team has according to the mission and vision, with the relevant stakeholders. During these workshops product/project dimensions like scope, technicalities, stakeholders community, estimations, risks, are discussed high level.

This phase is not successful finished, until the team has clearly and transparently defined its working agreements and ways of working and consolidated everything in a charter which is hung in the team room.

When teams are well designed and launched, we finally posed the basis for their stability and long-term value creation.

During the team journey, however, managers shall not forget to stay close to the team, supporting and coaching it to help passing through the process of transforming a group of people in a great team.